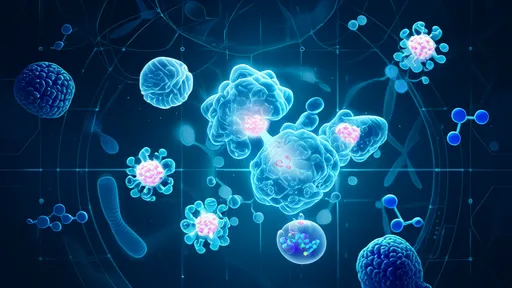

The Organ-on-a-Chip (OoC) Consortium represents a groundbreaking frontier in biomedical research, where miniature models of human organs are engineered to replicate the complexities of living systems. These microphysiological platforms are transforming how scientists study disease mechanisms, test drug efficacy, and evaluate toxicity—all while reducing reliance on animal testing. By mimicking the structural and functional nuances of human tissues, these chips offer an unprecedented window into human biology at a fraction of the scale.

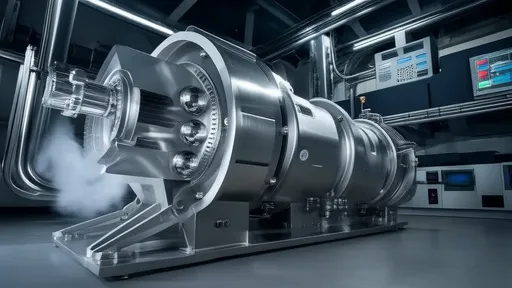

At the heart of this innovation lies the convergence of biology, engineering, and microfabrication. Each chip is typically composed of transparent polymers lined with living human cells, threaded with microfluidic channels that simulate blood flow and mechanical forces like breathing or peristalsis. For instance, a lung-on-a-chip might incorporate alveolar cells alongside capillary cells, separated by a porous membrane to recreate the air-blood barrier. When exposed to pathogens or pharmaceuticals, these systems respond much like a human organ would, providing real-time data on cellular behavior.

The implications for personalized medicine are profound. Researchers can now populate chips with patient-derived cells to predict individual responses to therapies. A cancer patient’s tumor cells, cultured on a chip, could help oncologists identify the most effective chemotherapy regimen before administration. Similarly, chips modeling liver metabolism might reveal how a drug is processed differently across ethnic groups or genetic profiles—a leap toward eliminating adverse reactions that often surface only during late-stage clinical trials.

Beyond drug development, organ chips are unraveling mysteries of human physiology. A brain-on-a-chip recently illuminated how inflammatory signals from gut microbiota may contribute to neurodegenerative diseases. Another study using a multi-organ chip demonstrated the cascading effects of a heart drug on liver function, something traditional Petri dish cultures would miss entirely. These interconnected systems hint at a future where entire "human-body-on-a-chip" platforms could model systemic diseases like diabetes or sepsis with startling accuracy.

Ethical considerations remain pivotal. While organ chips reduce animal testing—a goal long advocated by ethicists—questions arise about sourcing human cells and data privacy. The consortium addresses these through strict protocols, ensuring donor consent and anonymization. Moreover, as these technologies inch closer to regulatory acceptance (the FDA has begun evaluating chip-derived data for toxicity assessments), standardization becomes critical. Variability in chip design and cell sources could skew results, prompting the consortium to establish uniform benchmarks across labs worldwide.

Investment trends underscore the technology’s potential. Pharmaceutical giants like Johnson & Johnson and Roche now integrate organ chips into their R&D pipelines, slashing costs associated with failed drug candidates. Startups specializing in niche applications—such as mimicking the blood-brain barrier for neuro drug testing—are attracting venture capital. Meanwhile, government agencies like NIH and DARPA fund large-scale projects to link multiple organ systems, aiming to replace animal models entirely within the next decade.

Yet challenges persist. Reproducing organ-specific environments—like the mechanical stretch of a beating heart or the shear stress of blood flow—requires precision engineering. Cells cultured outside the body often lose functionality over time, limiting long-term studies. The consortium actively collaborates with material scientists to develop biomimetic scaffolds and nutrient delivery systems that extend cell viability, pushing the boundaries of how long these mini-organs can "live" in the lab.

Education and workforce training form another cornerstone. As adoption spreads, demand surges for researchers skilled in both biology and microengineering—a rare hybrid expertise. Universities are responding with interdisciplinary programs, while the consortium offers open-access design blueprints and training modules to democratize access. Their annual hackathons invite engineers and biologists to co-create solutions, such as a low-cost chip for malaria research in resource-limited settings.

The global impact is already visible. During the COVID-19 pandemic, lung chips infected with SARS-CoV-2 revealed how the virus triggers cytokine storms—a finding that informed treatment protocols. Now, teams are modeling long COVID effects on vascular and neural tissues. Climate change research also benefits: liver chips exposed to wildfire smoke contaminants have identified previously unknown metabolic disruptions, influencing public health guidelines.

Looking ahead, the Organ-on-a-Chip Consortium envisions a paradigm shift. Imagine clinical trials conducted first on chips housing a diverse "population" of human cells, predicting outcomes across demographics before a single volunteer is dosed. Or emergency rooms stocking chips tailored to a patient’s genetics for instant drug compatibility checks. As these tiny laboratories evolve, they promise not just to supplement but to redefine our approach to understanding—and healing—the human body.

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025