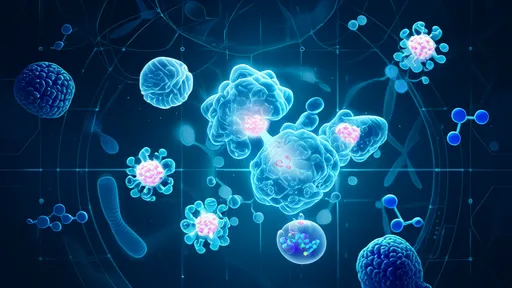

Chronic inflammation has long been a formidable adversary in modern medicine, implicated in diseases ranging from rheumatoid arthritis to cardiovascular disorders. Traditional treatments often rely on pharmaceuticals that come with a host of side effects. But what if the body’s own electrical wiring could be tapped to control inflammation? Emerging research into vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) suggests this might not only be possible but could revolutionize how we treat inflammatory conditions.

The vagus nerve, the longest cranial nerve in the body, serves as a critical communication highway between the brain and major organs. It plays a pivotal role in regulating the parasympathetic nervous system, which governs rest, digestion, and—importantly—immune response. Scientists have discovered that electrically stimulating this nerve can significantly reduce inflammation by modulating the body’s cytokine production. This breakthrough has opened the door to non-pharmacological interventions for chronic inflammatory diseases.

How Does Vagus Nerve Stimulation Work?

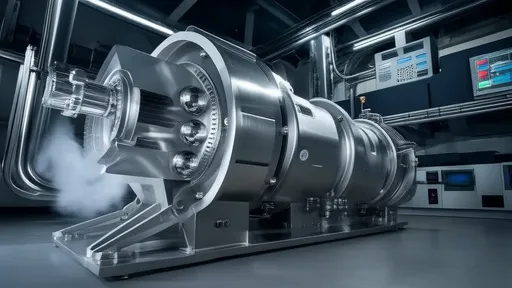

At its core, VNS involves delivering mild electrical pulses to the vagus nerve, typically through an implanted device. These pulses travel along the nerve fibers, reaching organs like the spleen and liver, where they trigger a cascade of anti-inflammatory signals. One key mechanism is the suppression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), a cytokine notorious for driving excessive inflammation. By dampening TNF-α and other pro-inflammatory molecules, VNS can restore balance to an overactive immune system.

Early clinical trials have shown promise, particularly in conditions like Crohn’s disease and rheumatoid arthritis. Patients who were unresponsive to conventional therapies experienced measurable reductions in inflammation markers after VNS treatment. Unlike immunosuppressants, which blunt the entire immune system, VNS appears to offer a more targeted approach, minimizing collateral damage to the body’s defenses.

The Science Behind the Signal

The therapeutic effects of VNS hinge on what scientists call the "inflammatory reflex." This reflex is a neural circuit that detects inflammation and sends signals to the brain, which in turn activates anti-inflammatory pathways. Electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve essentially hijacks this reflex, amplifying its natural ability to quell inflammation. Animal studies have demonstrated that cutting the vagus nerve eliminates this effect, underscoring its central role in immune regulation.

Human studies are now catching up. In one landmark trial, rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with VNS showed a 30% reduction in disease activity compared to controls. Imaging studies revealed decreased inflammation in affected joints, corroborating patient-reported improvements in pain and mobility. These findings have spurred interest in expanding VNS to other inflammatory conditions, such as lupus and even neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s, where inflammation is a known contributor.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite its potential, VNS is not without hurdles. The current gold standard involves surgical implantation of a stimulator device, which carries risks like infection or nerve damage. Researchers are exploring non-invasive alternatives, such as transcutaneous VNS, which delivers pulses through the skin. While less precise, early results suggest it may still confer anti-inflammatory benefits, making the therapy more accessible.

Another challenge is individual variability. Not all patients respond equally to VNS, likely due to differences in nerve anatomy or baseline inflammation levels. Personalized stimulation protocols, guided by biomarkers, could help optimize outcomes. Meanwhile, advances in bioelectronics may lead to smarter, adaptive devices that fine-tune stimulation in real time based on physiological feedback.

A Paradigm Shift in Inflammation Management?

If VNS continues to prove effective, it could herald a new era in treating chronic inflammation—one that moves away from pills and injections toward bioelectronic medicine. The implications are profound, not just for patients but for healthcare systems burdened by the cost of long-term drug therapies. As research progresses, the vagus nerve may well become a cornerstone of 21st-century medicine, proving that sometimes, the best way to heal the body is to work with its own electrical language.

For now, the field is ripe with possibilities. From refining device technology to uncovering new applications, the journey of vagus nerve stimulation is just beginning. One thing is clear: in the fight against chronic inflammation, electricity might be the most unexpected—and promising—weapon yet.

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025