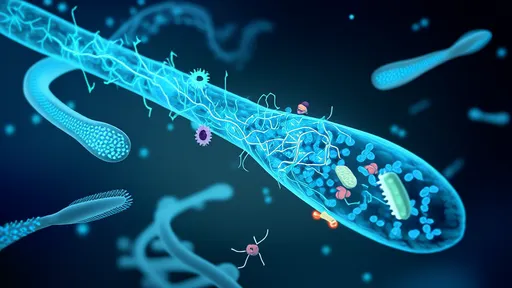

The bustling underground metropolises of leafcutter ants have long fascinated biologists, not just for their architectural complexity but for their sophisticated agricultural practices. These tiny farmers cultivate fungal gardens, their primary food source, in a remarkable symbiosis that dates back millions of years. What’s even more astonishing is their ability to manage antibiotic use to protect their crops from parasitic infections—a feat that rivals human agricultural technology.

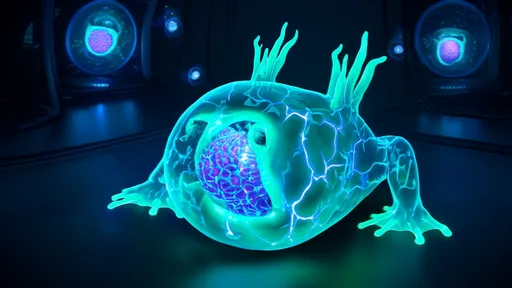

Deep within their subterranean chambers, leafcutter ants face a constant threat: the fungus Escovopsis, a destructive parasite that can decimate their fungal gardens. To combat this, the ants have developed a multi-layered defense system. They employ beneficial bacteria, housed in specialized structures on their bodies, which produce potent antibiotics. These antimicrobial compounds selectively target the parasite while sparing their cultivated fungus. This precision strikes a delicate balance, avoiding the pitfalls of antibiotic resistance that plague modern medicine.

The ants’ approach to antibiotic management is strikingly proactive. Worker ants continuously monitor the health of their fungal gardens, removing infected portions with surgical precision. They also adjust the composition of their bacterial allies, fostering strains most effective against current threats. This dynamic system ensures that their antibiotic arsenal remains effective, a lesson humans are still struggling to learn in the era of superbugs.

What makes this system even more remarkable is its sustainability. Unlike human agriculture, where antibiotics are often overused, leading to resistance, the ants’ system has remained stable over evolutionary timescales. Their secret lies in diversity—maintaining a variety of bacterial strains that produce different antibiotics. This redundancy prevents any single parasite from adapting to overcome their defenses.

Recent research has uncovered another layer to this system. The ants’ fungal crops themselves play an active role in disease suppression. By altering their chemical environment, the fungi encourage the growth of protective bacteria while inhibiting pathogens. This tripartite symbiosis—ants, fungi, and bacteria—functions as a tightly integrated superorganism, with each component fine-tuned through coevolution.

Scientists are now looking to these tiny pharmacists for inspiration. The ants’ ability to cultivate and harness beneficial microbes could inform new approaches to sustainable agriculture and antibiotic development. Their system demonstrates how to wield antimicrobials without triggering resistance—a blueprint that could revolutionize how we manage infections in crops and even humans.

Beyond practical applications, leafcutter ants offer a humbling perspective on our place in nature. Their 50-million-year head start in antibiotic management highlights how much we still have to learn from Earth’s smaller inhabitants. As we face growing challenges from drug-resistant pathogens, these insect farmers remind us that sometimes the most advanced solutions are those refined by evolution over millennia.

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025