The ocean’s depths hide mysteries that ripple far beyond the abyss, shaping life at the surface in ways we’re only beginning to understand. Among these enigmatic processes is the whale pump—a phenomenon where leviathans of the deep ferry nutrients upward, sustaining the microscopic engines of marine ecosystems. This silent exchange between giants and plankton reveals a delicate interdependence, one that challenges our perception of the ocean’s food web.

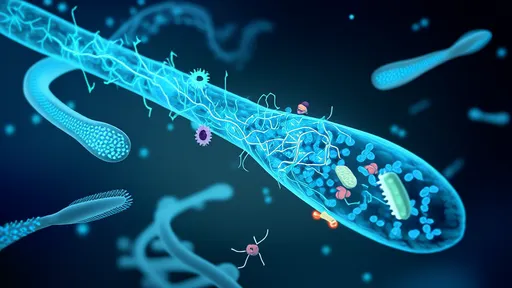

When whales dive, they embark on journeys that defy the limits of human endurance, plunging hundreds of meters in search of squid and krill. But it’s their return to the surface that sets the stage for an ecological ballet. As they breach, exhale, and defecate, they release plumes of nitrogen and iron-rich waste—a potent cocktail suspended in the photic zone where sunlight penetrates. Here, in this golden stratum, phytoplankton thrive, their photosynthetic machinery hungry for the very nutrients whales provide.

The significance of this transaction cannot be overstated. Phytoplankton are the unsung heroes of planetary health, producing over half the world’s oxygen while forming the base of marine food chains. Their blooms, often visible from space, trace the migratory routes of whales like ghostly fingerprints. Researchers have observed higher concentrations of these microorganisms in regions frequented by cetaceans, suggesting a feedback loop honed by evolution. The whales feed on deep-sea prey, ascend to breathe, and inadvertently fertilize the gardens that will eventually nourish their own offspring.

Modern technology has allowed scientists to quantify this relationship with startling precision. Satellite imagery combined with whale tracking data reveals nutrient plumes persisting for hours after a pod’s passage. Currents disperse these patches across dozens of kilometers, creating ephemeral oases where zooplankton congregate, drawing fish, seabirds, and even other whales into a temporary banquet. It’s a mobile, dynamic system—one that commercial whaling may have disrupted on a global scale before we recognized its existence.

The vertical migration of whales thus stitches together disparate layers of the ocean. Their bodies become conduits between the abyssal darkness where nutrients accumulate and the sunlit shallows where life proliferates. This process gains urgency in iron-limited regions like the Southern Ocean, where whale feces may historically have played a disproportionate role in maintaining productivity. Some models suggest pre-whaling populations circulated enough iron to boost phytoplankton growth by 15%, potentially sequestering millions of tons of atmospheric carbon annually.

Yet the whale pump operates on a timetable written in millennia, one that modern anthropogenic pressures have thrown into disarray. Ship strikes, entanglement, and underwater noise pollution now compound the lingering effects of 20th-century hunting. Conservationists emphasize that protecting these animals isn’t just about preserving charismatic megafauna—it’s about safeguarding a biological mechanism that shapes global biogeochemical cycles. The same currents that once carried whaling ships now bear witness to a slow recovery, as restored populations resume their ancient role as ecosystem engineers.

What emerges from this understanding is a portrait of the ocean as a living mosaic, where the largest creatures are inextricably linked to the smallest. The whale pump exemplifies nature’s circular economy, where waste becomes sustenance and movement translates into fertility. As climate change alters marine environments, this delicate dance may prove more vital than ever—a reminder that the survival of giants depends on the vigor of microbes, and vice versa, in an endless blue reciprocity.

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025