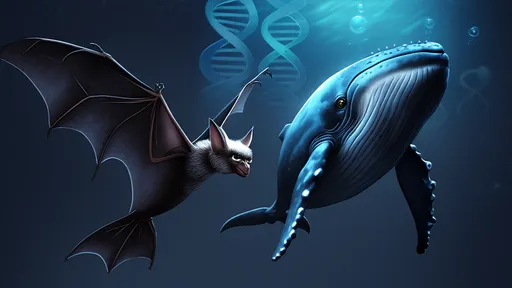

For decades, scientists have marveled at the uncanny ability of bats and toothed whales to navigate and hunt using biological sonar. Though separated by millions of years of evolution, these creatures developed strikingly similar echolocation systems independently—or so we thought. Groundbreaking research now reveals a deeper connection: shared genetic machinery underlying their acoustic superpowers.

The discovery challenges long-held assumptions about convergent evolution, the process where unrelated species develop analogous traits. While superficial similarities between bat and whale sonar were well documented, the new findings published in Nature Genomics demonstrate unexpected molecular parallels. "We're seeing something far more profound than functional resemblance," explains lead researcher Dr. Lin Wei of the Shanghai Institute of Biological Sciences. "These animals appear to have co-opted the same ancient genetic toolkit."

Echoes in the DNA

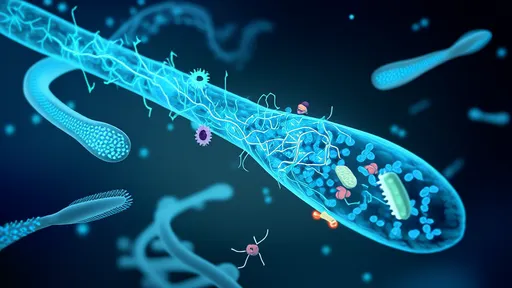

By comparing the genomes of 37 bat species and 14 toothed whale species, the international team identified 38 genes showing identical selection pressures in both groups. Particularly striking were modifications to Prestin, a motor protein crucial for high-frequency hearing. The protein's mutations followed nearly identical evolutionary paths in echolocating bats and whales despite their last common ancestor living over 65 million years ago.

Even more surprising was the involvement of developmental genes typically associated with limb formation. "We found echolocation-linked mutations in Hox genes—the same genes that help pattern wings and flippers during embryonic growth," notes co-author Dr. Maria Fernandez from the University of Barcelona. This suggests deep evolutionary connections between sensory systems and appendage development that transcend species boundaries.

An Ancient Acoustic Blueprint

The research points to a remarkable evolutionary scenario. Rather than inventing sonar from scratch, both bats and whales appear to have tapped into pre-existing genetic networks dating back to their terrestrial ancestor. These latent acoustic adaptations may have originally served different purposes before being repurposed for echolocation in their respective lineages.

Paleogeneticist Dr. Henry Park proposes an intriguing explanation: "Early mammals were likely nocturnal creatures relying heavily on sound. The genomic foundations for advanced hearing might have been present in our tiny, shrew-like ancestors." This genetic "starter kit" could have facilitated the later emergence of sophisticated sonar systems when bats took to the skies and whales returned to the seas.

Implications Beyond Biology

The findings extend beyond academic curiosity. Understanding these genetic mechanisms could inspire new biomedical technologies. "The Prestin protein's efficiency at converting electrical signals to mechanical vibrations is unparalleled," says bioengineer Dr. Rachel Goldstein. "Harnessing its principles might revolutionize hearing aids or underwater communication systems."

Conservation efforts may also benefit. With many echolocating species threatened by human activity, identifying their crucial genetic vulnerabilities could inform protection strategies. As climate change alters soundscapes across ecosystems, preserving these acoustic specialists becomes increasingly urgent.

As the research continues, scientists are expanding their investigations to other echolocating creatures like shrews and oilbirds. Each new genome sequenced adds pieces to this evolutionary puzzle, revealing nature's ingenious capacity for reinventing solutions across distant branches of life's tree. The silent conversations between bats and whales, written in their DNA, remind us that biological innovation often works with borrowed tools.

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025