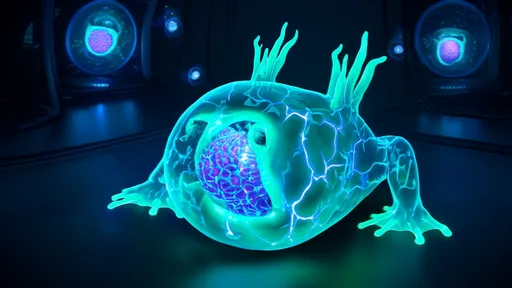

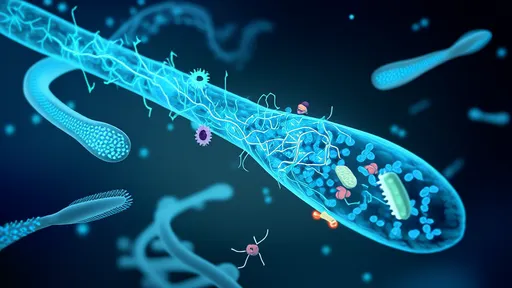

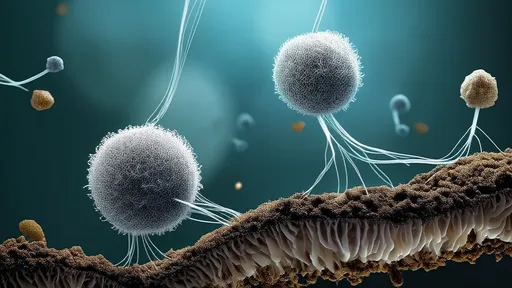

In the shadow of climate summits and carbon credit markets, an unassuming ally emerges from the forest floor. Mycelium—the vast, subterranean neural network of fungi—has begun capturing scientific attention for its potential to rewrite our approach to carbon sequestration. Recent studies suggest these intricate fungal systems may serve as Earth's forgotten carbon sinks, operating on a scale that could complement technological solutions to atmospheric CO2 accumulation.

The quiet revolution unfolds beneath our feet. Mycorrhizal networks, those symbiotic partnerships between fungi and plant roots, have been found to allocate up to 20% of a host plant's photosynthetic carbon into long-term storage in soil. This isn't mere nutrient exchange—it's a sophisticated carbon banking system developed over 450 million years of coevolution. Researchers at the Society for the Protection of Underground Networks (SPUN) estimate that existing fungal networks already sequester approximately 13 gigatons of CO2 annually, equivalent to one-third of human emissions.

What makes mycelium extraordinary isn't just its carbon appetite, but its storage mechanism. Unlike above-ground biomass that releases carbon upon decomposition, fungal networks incorporate carbon into stable glycoproteins like glomalin. This "fungal glue" can persist in soils for decades, forming carbon-rich aggregates that resist microbial breakdown. The Hubbard Brook Ecosystem Study revealed forest soils with intact mycelial networks contain 50-70% more carbon than those where fungi have been disrupted by agriculture or deforestation.

The implications for climate strategy are profound. While tech companies race to build direct air capture facilities costing $600 per ton, fungal networks perform sequestration at negative cost—enhancing soil fertility as they work. Dr. Merlin Sheldrake's fieldwork in Panama demonstrated that inoculating degraded soils with native fungal strains accelerated carbon storage rates by 300% within five years compared to conventional reforestation. "We're not just planting trees," he notes, "we're rebuilding the ancient carbon partnerships that made terrestrial life possible."

Agricultural applications are already yielding results. Trials using fungal amendments in Brazilian soybean fields increased soil carbon by 8 tons per hectare while reducing synthetic fertilizer needs. California vineyards employing mycorrhizal inoculants report both deeper carbon sequestration and increased drought resistance—a critical advantage in warming climates. "The vines tap into fungal water channels during dry spells," explains viticulturist Elena Cortez. "But we're only now realizing their carbon capture potential."

Challenges remain in scaling fungal solutions. Unlike standardized mechanical capture systems, fungal networks require ecosystem-specific approaches. The wrong fungal strain can become invasive, while overharvesting commercial mycorrhizal products threatens wild fungal populations. The Fungi Foundation's Global Mycorrhizal Catalog initiative seeks to address this by mapping regional fungal "fingerprints" to guide restoration efforts. Meanwhile, questions persist about measurement protocols—current soil carbon assessments often miss the fungal contribution entirely.

Policy frameworks are scrambling to catch up. The European Union's 2023 Soil Health Law became the first major legislation to recognize fungal networks as critical carbon infrastructure. In Canada, the MycoCarbon Project enables landowners to generate verified carbon credits through fungal-enhanced afforestation. Yet most carbon markets still favor above-ground biomass, creating what mycologist Dr. Suzanne Simard calls "a dangerous blind spot in our climate math."

The road ahead demands interdisciplinary collaboration. Geneticists are exploring fungal genome editing to enhance carbon-binding proteins, while materials scientists mimic mycelium's nanostructure for bioengineered carbon capture materials. Perhaps most crucially, indigenous knowledge systems—long attuned to fungal networks—are finally gaining recognition. The Māori-led Whenua Haumi project in New Zealand has achieved remarkable carbon storage by integrating traditional fungal cultivation with modern mycology.

As the climate crisis intensifies, fungal solutions offer something rare: a strategy that works with Earth's systems rather than against them. From the arctic tundra's dark fungal mats to the sprawling mycelial webs beneath tropical rainforests, these ancient lifeforms have been regulating carbon cycles since before humans walked upright. The question isn't whether we should incorporate fungi into climate mitigation—it's whether we can afford not to.

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025