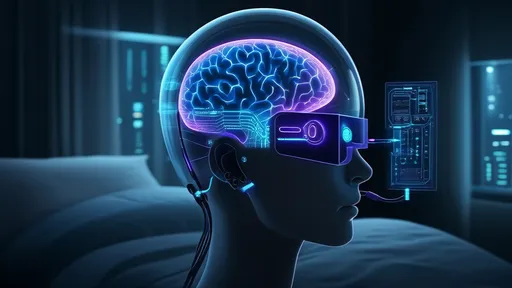

The field of neurobiology has long been fascinated by the concept of empathy—how humans and some animals can understand and share the emotions of others. At the heart of this discussion lies the mirror neuron system (MNS), a network of neurons first discovered in macaque monkeys in the 1990s. These neurons fire both when an individual performs an action and when they observe another performing the same action, suggesting a neural basis for imitation and, by extension, empathy. However, decades later, the role of mirror neurons in human empathy remains hotly debated.

Early Discoveries and High Hopes

When Italian neuroscientist Giacomo Rizzolatti and his team at the University of Parma first identified mirror neurons, the scientific community erupted with excitement. Here, it seemed, was the biological foundation for social cognition—the mechanism that allowed humans to "mirror" each other's emotions and intentions. Early studies suggested that mirror neurons could explain everything from language development to autism spectrum disorders. The idea was elegant: by simulating others' actions internally, we could intuitively grasp their feelings and motivations.

Functional MRI (fMRI) studies appeared to support this. When subjects watched videos of people expressing emotions, brain regions believed to house mirror neurons—such as the inferior frontal gyrus and superior temporal sulcus—lit up. This seemed to confirm that humans possessed a similar system to macaques, one that enabled emotional resonance. The mirror neuron theory quickly gained traction in psychology, neuroscience, and even philosophy, becoming a popular explanation for the human capacity for empathy.

The Cracks in the Mirror

As research expanded, however, inconsistencies emerged. Critics pointed out that fMRI could not directly measure individual neurons, only blood flow changes in broad brain regions. This made it impossible to confirm whether the activated areas truly contained mirror neurons or were simply involved in broader social processing. Meanwhile, single-neuron recordings in humans—rare due to their invasiveness—failed to consistently replicate the mirroring properties seen in macaques.

Perhaps most damaging were studies of patients with brain lesions. If mirror neurons were indispensable for empathy, damage to these networks should severely impair emotional understanding. Yet patients with lesions in supposed mirror neuron regions often retained normal empathy, while those with intact mirror systems sometimes showed profound social deficits. This suggested that empathy relied on a much broader neural network than the MNS alone.

Alternative Explanations Gain Ground

As doubts grew, alternative theories emerged. Some researchers proposed that what appeared as "mirroring" might actually be predictive coding—the brain's way of anticipating others' actions based on statistical learning rather than direct simulation. Others argued that empathy involved top-down processes, where higher cognitive areas interpreted sensory input to infer emotions, rather than automatic mirroring.

Notably, a 2021 meta-analysis in Nature Neuroscience found that while certain brain areas consistently activated during empathy tasks, their activity patterns didn't align neatly with the mirror neuron hypothesis. Instead, empathy appeared to recruit distributed networks involving the anterior insula, anterior cingulate cortex, and medial prefrontal cortex—regions associated with interoception (sensing one's own bodily states) and mentalizing (theorizing about others' minds).

The Current Consensus—and Unanswered Questions

Today, most researchers agree that mirror neurons likely contribute to basic motor mimicry and low-level emotional contagion (like wincing at someone's pain). However, higher-order empathy—complex emotional understanding and compassion—probably requires integration across multiple systems. The MNS may be one piece of this puzzle, but not the sole mechanism.

Debates continue about methodological limitations. Without finer-grained tools to track individual neuron activity in awake humans, the mirror neuron hypothesis remains difficult to prove or disprove definitively. Meanwhile, newer technologies like optogenetics and advanced computational models may eventually shed clearer light on how empathy truly operates in the brain.

What this controversy underscores is the complexity of human social cognition. Empathy is unlikely to be reducible to a single neural system. Instead, it emerges from dynamic interactions between perception, memory, emotion, and reasoning—a symphony of brain activity that science is only beginning to decode.

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025